See first: AI: Part 1 and AI: Part 2

A Conversation with Edel Rodriguez

Marian: Given my previous post, I’d like to start this off by asking you if you stand by your (and the Society of Illustrators’) position on this or if you have a modified opinion.

Edel: The Society of Illustrators’ statement was made by the museum’s staff in order to make their position clear on how AI images would be treated during their annual competitions. This is just one of the many ethical questions that come up when machines are used to generate art: Is it fair to give awards or accolades to artwork that is generated by typing words into a computer? Is it fair to give awards to artwork that is generated using the work of living artists as guide? Work that was input into the AI programs without the consent of those artists?

There was an article in The New York Times about someone that won a prize at a competition. The art was generated using Midjourney and the submitter did not notify the competition that it was generated by Midjourney’s stable diffusion software. Since there were no rules in place, he felt he had not violated any rules. This brought up many questions for other art and illustration competitions. Many of them have come out with statements that submitting AI generated images will not be allowed.

I agree with the position of The Society of Illustrators, who along with American Illustration and Communication Arts have made the decision that artificially manufactured images should not be considered for their exhibits.

M: I agree with you regarding contests (though I believe the landscape, the rules, and my opinion will change), although I dispute that living artists’ work is compromised because a) the AI systems take pieces from billions of images, of which artists’ work is minimal, b) it doesn’t regurgitate images or parts of images but creates anew from its amalgamated “understanding” of what things and styles are, and c) you can’t copyright style.

E: Marian, this software is at version 1.0. I think many of the technical issues you discuss will be tinkered with and ironed out in future versions.

The bigger issues are whether we should be handing artistic control to machines and whether we should allow these machines to scrape our data and portfolios for use as the foundation of their system. Art is about intent, what the artist decides to make. Here we have the machine telling you what art is.

If this entire conversation were about AI scraping the text from classic novels, a prompter writing a few words, the AI spitting out an entire novel, and the prompter calling that their work, everyone would be outraged. We are being distracted by silly and fun and slick images and letting go of how ethically dangerous this whole thing is.

M: I maintain, from talking to people and reading people like Rodney Brooks, who know the true limits of AI, that it is NOT intelligent, and its not going to get intelligent in the near future and perhaps never. Meaning it will get better at portraying horses, but still be unable to understand “horse typing at a desk,” which a human can easily do. This is a true limitation of AI. Meanwhile the “pollution” problem I talk about from fantasy art is very real. Now, that may get fixed by human tinkering, along with biases in representation of e.g. black people.

As for the scraping of data—again, you are thinking it’s targeting artists and it’s not—it’s taking everything, of which you and I are miniscule parts.

But most importantly, the machine is not telling us “what art is”—it’s not telling us anything at all, merely responding in images to words that it learned from thousands of images tagged or captioned with those words.

Also, novels … the text generating AIs are already “writing” novels which work on the same principle, but produce more coherent sentences because there’s so much more text on the internet, and it’s able to find contextual patterns that make it sound sensible. But it’s still not intelligent. Think of it as an advanced parrot—it appears to be saying things, and may appear to have a conversation, but it doesn’t understand and never will unless something radical happens to the parrot. That radical thing is what AI engineers have been looking for for decades, and each time they think they’ve made a leap, they hit a roadblock. Yes, they may find that radical thing that opens AI up to true understanding in our lifetime, or they may not, but it won’t come from the existing system of learning.

‘In the past, scientists unsuccessfully tried to create artificial intelligence by programming knowledge directly into a computer. Now they rely instead on “machine learning” techniques that let the computers themselves work out what to do based on the data they see. These techniques have led to amazing breakthroughs. For example, you can give a machine learning system millions of animal pictures from the web, each one labeled as a cat or a dog. Without knowing anything else about animals, the system can extract the statistical patterns in the pictures and then use those patterns to recognize and classify new examples of cats and dogs. […]

The problem is that these new algorithms are beginning to bump up against significant limitations. They need enormous amounts of data, only some kinds of data will do, and they’re not very good at generalizing from that data […]

the big recent advances haven’t primarily come about because of conceptual breakthroughs—the basic principles behind the machine learning algorithms were discovered back in the 1980s. The new development is that the internet now provides massive data sets for AIs to train with (everybody who has ever posted a LOLcats picture has contributed to the new AI) […]

AIs also need what computer scientists call “supervision.” In order to learn, they must be given a label for each image they “see” or a score for each move in a game. […] Even with a lot of supervised data, AIs can’t make the same kinds of generalizations that human children can. Their knowledge is much narrower and more limited, and they are easily fooled by what are called “adversarial examples.” For instance, an AI image recognition system will confidently say that a mixed-up jumble of pixels is a dog if the jumble happens to fit the right statistical pattern […]’

— Alison Gopnik “The Ultimate Learning Machines,” Wall Street Journal

E: Art is different from text because it can appear intelligent. So it doesn’t matter whether or not it is intelligent. What is on the surface “intelligent” or “logical” about much of Surrealism or Dada or abstract art? Much of it is a collection of random images or colors that can easily be duplicated by a non intelligent machine. An artist brought intent to that work and there are likely personal ideas within the work, but an A.I. program can easily work in those realms without having to know exactly where to place things. My issue is with the idea that someone typing in a few words can take the credit for the “creation” of a work of visual art. Many are doing so already. To top it off, they get outraged when someone asks them for their prompt or appears to mimic “their creation”.

M: So how is this different from someone without any skill whatsoever taking a photo? Or for me to ask, hey, where did you take that—I’d like to go and take one too?

FWIW I strongly believe that the use of AI should always be credited—as should the use of digital photo work. Imagine the following: “Wow! What a great painting!—oh, it’s a photo … well, still, nice photo—ah, you did some “work” on it … the clouds are from a different photo … and it has a “paintbrush filter added to it. OK …” I confess I have a strong bias toward art that is “hand made,” I’ve never cared for digital art, and the discovery that something I thought was made by hand is actually digital always disappoints me and devalues the work, in my eyes. But that’s partly a matter of taste, and it doesn’t mean the art is “not art.”

Anyone who tries to pass off a photo as a hyper-realistic painting is as guilty as anyone who passes off an AI image as a painting/whatever. Fakery is fakery, but the use of AI is not inherently so; only the lie that it is hand made would be.

If “ease of fabrication” or “only the masters hand” were in the code that defines “art”, then what about Pollock? Or minimalists? Or chinese calligraphers who complete a work in 3 strokes? Or duChamp’s found art? The old Masters who had apprentices finish their work? Or Damien Hirst (and many other contemporary artists) who get others to do their paintings? Collagists, photographers … the list goes on.

E: What defines art is the artist’s intent. The risks they take, the decisions they make. I have no interest in skill as defining art. I love the work of Duchamp, Warhol, Joseph Beuys, Sol Lewitt, and others who use existing material in their work or paint a couple of strokes and define it as art. Same with photography. Like a lot of photographers and do much of it myself.

I don’t see artistic intent with AI. I see an algorithm and diffusion software telling the artist what art is.

M: Of course there’s no artistic intent with AI, but neither is there any with a paintbrush or a camera. The camera really is the best analogy because it is a piece of technology that we use to represent things—in a multitude of different ways. We take a picture, don’t like it, change some settings, or the angle or our position, take another one, and another until we get something that pleases us. AI is exactly the same way only less controllable.

Jonathan Hoefler doesn’t get his images by typing in a few words and voila! He gets them by doing that over and over, adjusting and trying again, and again until he gets some things he’s happy with.

That camel in the weird lemon cup that I prompted—that’s insane, and by far the weirdest thing I got out trying and adjusting a prompt over and over—and what’s cool is it won’t do it again! I’d like to get other versions of that camel-in-a-plastic-lemon-cup but I can’t get it to make another one. (If using a camera is like learning to ride a horse, using AI is like learning to ride a wild horse.)

Yes, there are mountains of garbage produced by AI, because there are mountains of garbage produced by humans. But I think some people will find interesting ways to use it, and just because it came out of AI doesn’t mean there was no human intent or idea or process of creation.

‘During the First Neural “AI” Art Wave, “AI” art developed in a rapid cycle of new artists experimenting with new technologies as they emerge. Most “AI” artists needed some technical skill to find, download, run, and modify the latest experimental machine learning code shared by research labs. The best “AI” art came from artists building their own training datasets (e.g., Helena Sarin, Scott Eaton, Sofia Crespo) and/or directly modifying their models. Even “AI” artworks with a message were still very experimental.

With the new easy-to-use text-to-image models, we’re now in a new wave of people exploring these models and what they can do, and still a heavy wave of experimentation. These things are exciting because they are novel. I spent a fascinating month last May playing with DALL-E […].

When people (like art critic Ben Davis) accuse “AI” art of being focused on novelty, I say: of course it is. The dominant aesthetic of any new art-making technology is novelty. The only way you figure out art in a new medium is by experimentation. And, for many of us, it’s exciting to be there at the beginning, to know that something big is happening, even if you don’t know what.

New media first mimics existing media, then evolves.

The artists who first experiment with a medium often begin by mimicking existing new media. It takes a long time—sometimes decades—to figure out the unique properties of the new medium.’

E: Re “…images by typing in a few words and voila! He gets them by doing that over and over, adjusting and trying again, and again until he gets some things he’s happy with”: This sounds like shopping online until you find the right color of pants. The machine is feeding you options until you’re happy. People using this software to make things that look like art are cosplaying as artists.

A few thoughts on your last post. Regarding tapping into an artists style. Tomer Hanuka is a very well known illustrator. His work was input into AI and a whole collection of NFT’s was created in his style and sold as NFT’s using his name as the brand without his permission. He wrote about it here:

M: This is an egregious case, not because they copied his style, but because they claimed it was by him, using his name to sell things he never made.

E: I brought this up because it is a perfect example of copying the look of an artist’s work directly, something you mentioned was not possible. I’ve seen this multiple times. Is it copyright infringement? I don’t know. Copyright is handled on a case by case basis by the courts, and often settled out of court.

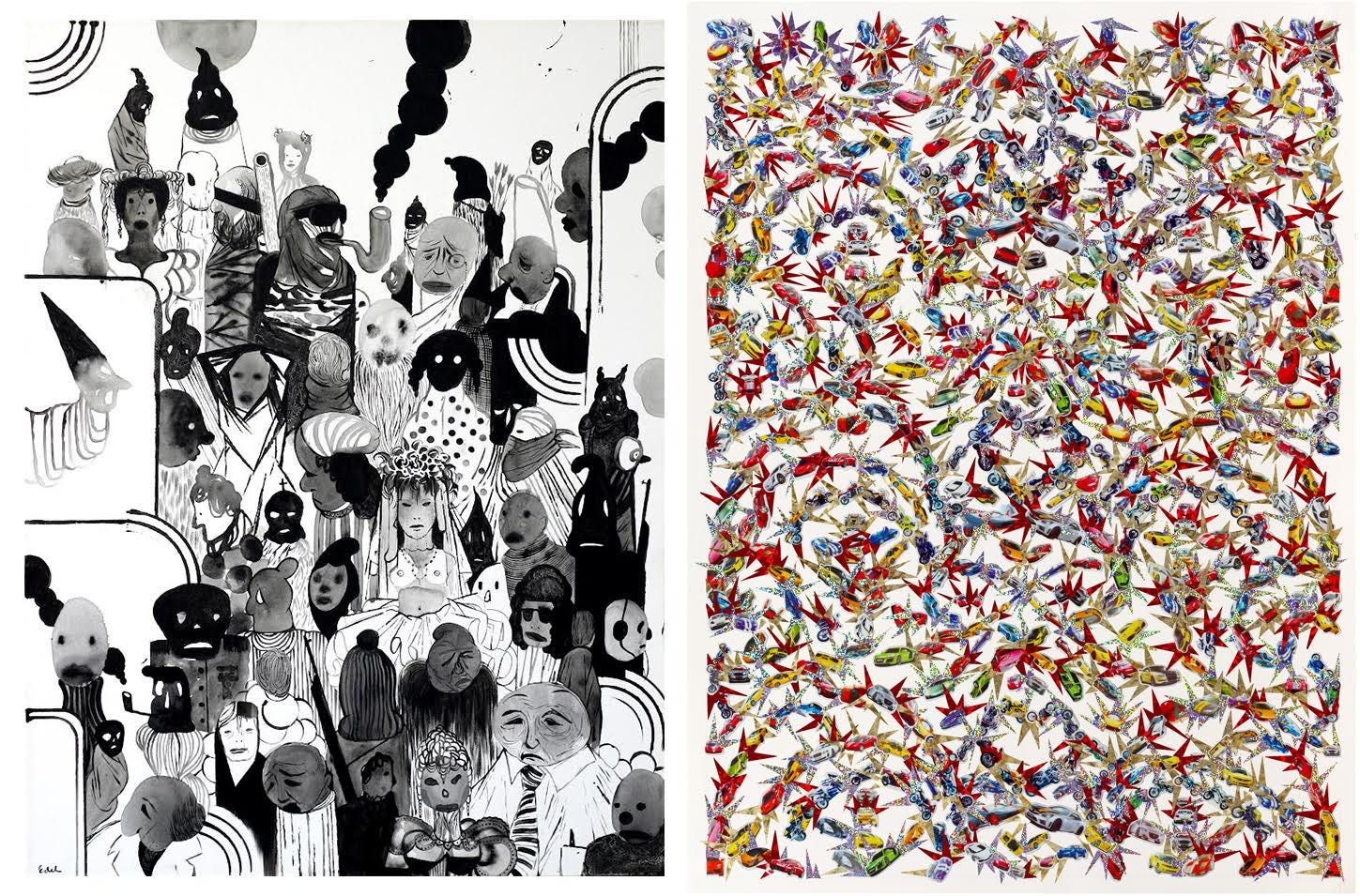

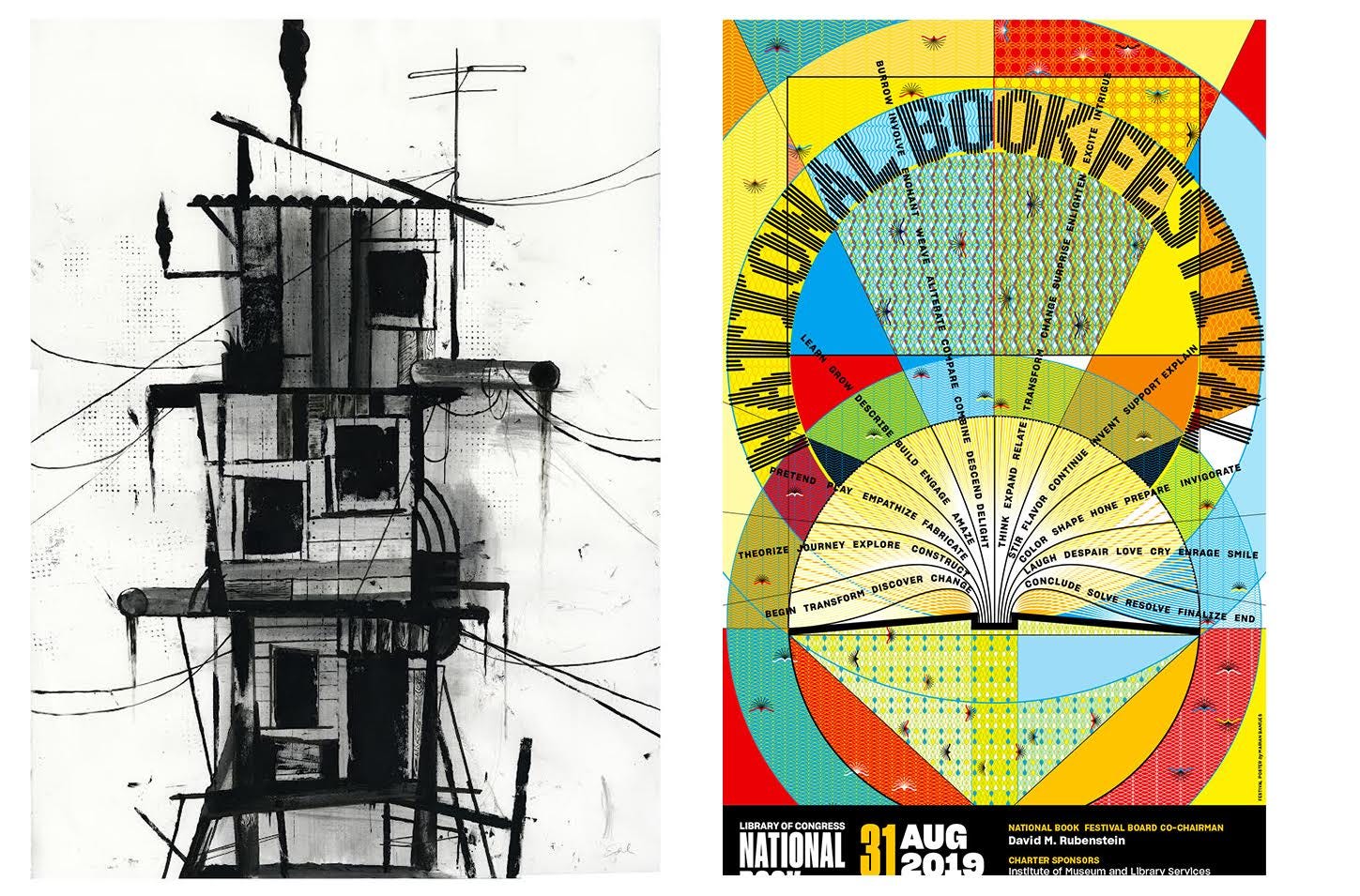

M: While I didn’t say it was “not possible”, this is a good case for how shallowly it interprets work. I confess I didn’t know who Tomer Hanuka was, so I took a closer look. Judging by the images he posted on Twitter of the “Punks [not by] Hanuka”, I had a completely different idea in my mind of what his work would look like. When I went to his website I was surprised and impressed. Also, of course I’ve seen his work before—particularly on the cover of the New Yorker, and recognized his TH signature (“Ahh, that’s who he is!”). But his actual work is so infinitely better, and what makes it good is fantastic composition, elements of surprise (repetitions, intentional glitches), unique characters, and a range of “styles”. The NFTs have none of that, and just look like a million other illustrated cyberpunks. Furthermore, we don’t know how they were prompted, or whether they used an image of his in the prompt. I maintain that the direct infringement of his name and the lie that the work is by him is the real issue.

E: Regarding your heart image [in Part 2]. This gets at my main concern. Any company can take your work and decide they want to make a 3D version of it for example. For a decorative item, a lamp cover, or an object of some sort. You mention that humans have tried to do this in the past with your work, but that takes time and commitment and that investment of time makes people not go through with the copying. AI doesn’t require the human effort and time to copy. Any company can input your work and get a result back in seconds, without even hiring someone.

M: but Edel, they don’t have anything they can make into a lamp; it’s just an image. And it’s a mess, and it’s not my work. They can attempt to make whatever they want that they think looks like my work—provided it isn’t actually my work. The machine is emulating three common things it’s familiar with: heart, ornament, cut out.

But, as noted in my piece, I agree this should not be legal. Not because it’s the closest it’s come to emulating my art (albeit still far) but because a) this is the type of thing it will improve at (emulating existing images) and b) it shows and encourages the intent to copy a specific piece of art.

E: Also, regarding your first post that AI doesn’t know how to put things on top or below, etc. I can see that part of the work being done in Photoshop by art directors. Render a bunch of horse paintings, render a bunch of jockey paintings, choose the ones that match, and photoshop them together. It’s very easy to clone and cleanup Midjourney 3D renderings and images.

M: Well here I think you’re on very shaky ground, because once a person starts making decisions about where to place images, moving them around, adjusting them in Photoshop, close cropping the damn things, blending them etc., you have “the hand of the human.” And this is precisely where the wedge is to open competitions etc. back up to including AI-images—blended into digital photography—and so it should.

Seriously, it’s not easy to clone and clean up anything. I’ve spent hours and hours and hours doing it recently for an artist’s book (not mine).

E: My issue is not with appropriation in art. I think it’s often correct and can be a bold statement. My issue is with Artificial Intelligence doing the appropriation, since it has no rhyme or reason for doing it. Artists that use existing material are doing it for conceptual reasons.

M: The machines are not entities and they have neither intent nor ability. This whole AI thing is part of 70+ year research by humans to understand and maybe replicate human intelligence. As noted above, these ‘machine learning’ experiments began in the 1980s, and only recently, due to faster computers, bigger storage and massive amounts of publicly available data that has accumulated on the internet (helped greatly in part by social media and the sharing of billions of images taken on phones (since approx. 2007), a 40-year-old idea is showing great progress. Due to the collection (by humans) of all this data and the machine’s programmed ability to recognize patterns—either in sentences or in pixels—it can now give a pretty good emulation of having a conversation. Then someone said “hey, what it can do with words, could it do it with images?” Then “could it discern “painting” from “photo”?”, and on and on.

Artists are the people that use the tool to make images of things that interest them. While most of it is “fantasy art”, and most of it is bad (imho), there are a few people who are exploring the AI image generators with artistic curiousity, with artistic intent, and who don’t just “type in a few words” and viola! I’m not sure if I’m one of these people, but I can say I have experimental intent—and 80% I reject outright, while 5% is an actual “Oh yeah, that’s great!” If I use them for anything, obviously I will credit Midjourney.

E: This is a story from June 2022 when Cosmo used Dall-E AI to make a cover:

M: This is interesting to me because a) it’s a sub-standard cover, and b) the claim, on the cover, that “it took only 20 seconds” is an outright lie.

In the article it says that in under an hour a cover is “close”. If you look at the outtakes, they’re far from the final.

The animation of the “outpainting” is done at high speed—in order for a human to have time to contemplate and select one of those options it would have to go much slower.

I wondered at the word “president” in their prompt “a strong female president astronaut warrior walking on the planet Mars.” Nothing about the image suggests “president” (but then what would? A lecturn? Medals? A flag?) but then I decided that they probably threw that in because they were just getting “sexy” astronauts and they were trying to figure out how to stop that. (Ditto, the word “warrior”—though it’s a miracle it doesn’t have a sword.)

The images in Midjourney (and, from what I’ve read DALL-E as well) are 1024x1024 — that’s offset printable at about 4x4, barely, so then it has to be upscaled in Photoshop or some other program and touched up, etc.

I would be very, very surprised if all this took less than 4 hours. What could you do in 4 hours? Better than that, I think. But of course, in an issue about AI, it only makes sense to have an image made in an AI program.

E: You mentioned work as being “substandard” or not very good, but none of that is what this is about for me. It’s not about how good at quality AI is, it’s that we’re accepting it at all. I feel that artists and designers have lost faith in themselves and put faith in machines. Software has made some things better in life, but plenty of things worse. I think it’s good to take a step back and ask, should we even be doing any of this? Should well known designers be hyping it online? As I said, this is version 1.0, and it’s evolving and moving very rapidly. These A.I. companies put out idealistic statements about “enhancing imagination” this and that, but they’re very foundation is theft for profit. I don’t want any part of it and neither should artists that respect their work and the work of their peers.

One thing I’d like to get into is about influences. Several people have compared AI to humans in that we see things, take them in and then bring them into our work, as they say AI does.

But that fails to account for human experience and how that experience is folded into our work, either purposely or in more subtle ways. We may be born in India, Cuba, Canada, Africa, etc., and those places, customs, climate and people show up in what we do in one way or another. Some of us are single, married, lgbtq, Black, Latino, have gone through deaths in the family, abuse, addiction, etc., and all of these things often make up our work. Jackson Pollock did’t just wake up at 35 and start throwing paint around. He spent years working on figurative work, went through personal struggles and addiction and eventually arrived at the work we know him for.

Almost every little bit you see in my work is attached in one way or another to some sort of personal experience. Sure, artists study drawing, painting, art history, and learn from past artists, but the essence of the work is a mix of the visual things we’ve learned mixed with our personal experiences. A.I. is strictly taking from the visual, it’s all surface. It has no personal experience or history to give the work any kind of depth or meaning. And that is one of the main reasons I don’t consider it to be art.

M: Well, I agree with you up to a point on this, particularly about the well that AI draws from being all surface—the only thing it’s doing is recognizing patterns in pixels, after all, and we should expect no more of it. This is why it can’t “replace” artists. But inasmuch as it’s a tool, and artists who use it recognize something in what they dredge up from it, that’s where any “soul” might come from—not soul in the machine but soul from the artist. Imagine an artist trying to interpret a dream by putting words into prompts, or using a couple of words that evoke their feelings (“hollow chest,” or “under the bed,” or “lost”)—if the machine produces one or some images that speak to that person’s feeling, why would that be illegitimate? But it requires the human to prompt, to recognize, and perhaps transform what they get.

Ultimately, I think artists and designers should put way more faith in themselves, in their ability to understand concepts and create abstract ideas, to invest soul and humour and surprise into their work, and their ability to see the real world and extract visions from it. I think that text-to-image machines will be incorporated into some people’s art in interesting ways, while much of it will be the same dross as the billions of selfies and snapshots people take on their phones every day. While I’m worried for artists who rely on creative directors for work, I’m not worried about art or artists’ eternal ability to express themselves, no matter what method they use.

Some links:

Aaron Hertzman, “When Machines Change Art.”

Aaron Hertzman, “Can Computers Create Art?”

Forbes, “Midjourney Founder David Holz On The Impact Of AI On Art, Imagination And The Creative Economy.”

Alison Gopnik, Wall Street Journal, “The Ultimate Learning Machines.”

Rodney Brooks, “Predictions Scorecard 2023”

Rodney Brooks, “The Seven Deadly Sins of Predicting the Future of AI.”

Rodney Brooks, “Steps toward a Superintelligence III: Hard Things Today.”

Steven Heller, Print Magazine, “There’s Nothing Artificial About AI Type Design.”

Eliza Strickland, iEEE Spectrum, , “DALL-E 2’s Failures are the Most Interesting Thing About It.”

Bloomberg Law “Copyright Office Sets Sights on Artificial Intelligence in 2023.”

I agree with all that you have written, Marian. I wish more design and illustration community leaders were brave as you are to experiment with and articulate an unemotional opinion regarding the technology. I am disappointed and disturbed by the reactions of the illustration community. No AI can reproduce Edel's work. And as you have demonstrated, it can't mimic any specific artist's work in any way, much less consistently and reproducibly. The areas where it can mimic "style" are often areas where the style is so typical that the AI is mimicking MANY artists. If mimicking style was as big a problem as some claim, what about artists who have aped the styles of many other illustrators? In my lifetime, many of my favorite illustrators–Norman Rockwell. Frank Frazetta. Franklin Booth. Bernie Wrightson have been widely imitated. Minor or significant artists, fine or commercial artists, "influences" are matter-of-fact. These artists have been borrowed from and, quite convincingly, in many cases.

The community questions morality, ethics, and legal questions.

Moral arguments are complicated because morality is strictly personal, for better or worse. If the matter is one of "soul" or "humanness," these are issues for the individual "creator." Suppose it is an ethical question (as it certainly is in some instances). In that case, this is a question governed by the community– and is already addressed by the profession (as evidenced by the position of various competitions). As you have indicated, legal issues will evolve with the technology and the marketplace.

The fear of technology is the core of all of the arguments. All other views only mask the anxiety that seems to be gripping a large portion of the community. The outrage is not unexpected but is a waste of intellectual and emotional energy.

The best example of technology changing art is "sampling" in the music industry. It was generally subtle and tolerated at first. Still, it became egregious, was settled as a legal issue, and now seems to be the currency of the profession and considered "creative." In my opinion, very little of the music created this way is appealing OR creative. The marketplace disagrees with me.

As far as the loss of jobs by artists, this will undoubtedly happen. Technology does this. There are examples throughout history of which we are all aware. Within the design community, look at typography and typesetting in the late '80s and '90s. Desktop publishing decimated that industry. And we still suffer from bad "typesetting."

On the other hand, technology lowered the barrier to entry for designing a font. Type design software created tremendous creative opportunities for type designers and led to remarkable technical advances (see Opentype). We are in a Golden Age of innovative typographic design.

It's time to calm down and find ways to use this technology to our advantage. We will all benefit if we look at this as another tool instead of a threat. Stop catastrophizing. Technology happens, and intelligent practitioners have survived and thrived.